- Home

- Safiya Umoja Noble

Algorithms of Oppression

Algorithms of Oppression Read online

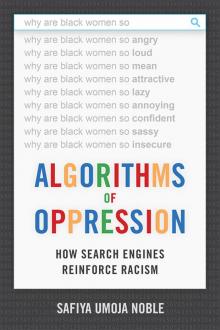

ALGORITHMS OF OPPRESSION

Algorithms of Oppression

How Search Engines Reinforce Racism

Safiya Umoja Noble

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

© 2018 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN: 978-1-4798-3364-1 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Noble, Safiya Umoja, author.

Title: Algorithms of oppression : how search engines reinforce racism / Safiya Umoja Noble.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017014187| ISBN 9781479849949 (cl : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781479837243 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Search engines—Sociological aspects. | Discrimination. | Google.

Classification: LCC ZA4230 .N63 2018 | DDC 025.04252—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017014187

For Nico and Jylian

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Power of Algorithms

1. A Society, Searching

2. Searching for Black Girls

3. Searching for People and Communities

4. Searching for Protections from Search Engines

5. The Future of Knowledge in the Public

6. The Future of Information Culture

Conclusion: Algorithms of Oppression

Epilogue

Notes

References

Index

About the Author

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to acknowledge the support of the many people and organizations that made this research possible. First, my husband and life partner, Otis Noble III, is truly my most ardent and loving advocate and has borne the brunt of what it took for me to write this book and go around the country sharing it prior to its publication. I am eternally grateful for his support. For many years, he knew that I wanted to leave corporate America to pursue a Ph.D. and fulfill a lifelong dream of becoming a professor. When I met Otis, this was only a concept and something so far-fetched, so ridiculously impossible, that he set a course to make it happen despite my inability to believe it could come true. I am sure that this is the essence of love: the ability to see the best in others, to see the most profound, exceptional version of them when they cannot see it for themselves. This is what he did for me through the writing of this book, and somehow, given all the stress it has put us under, he has continued to love me each day as I’ve worked on this goal. I am equally indebted to my son, who gives me unwavering, unconditional love and incredible joy, despite my flaws as a parent and the time I’ve directed away from playing or going to the pool to write this book. I am also grateful to have watched my bonus-daughter grow into her own lovely womanhood through the many years I’ve spent becoming a scholar. I hope that you realize all of your dreams too.

My life, and the ability to pursue work as a scholar, is influenced by the experiences of moving to the Midwest and living and loving in a blended family, with all its joys and complexities. This research would not be nearly as meaningful, or even possible, without the women and girls, as well as the men, who have become my family through marriage. The Nobles have become the epicenter of my family life, and I appreciate our good times together. My many families, biological, by marriage, and by choice, have left their fingerprints on me for the better. My sister has become a great support to me that I deeply treasure; and my “favorite brother,” who will likely have the most to say about this research, keeps me sharp because we so rarely see eye to eye on politics, and we love each other anyway. I appreciate you both, and your families, for being happy for me even when you don’t understand me. I am also grateful to George Green and Otis Noble, Jr., for being kind and loving. You were, and are, good fathers to me.

My chosen sisters, Tranine, Tamara, Veda, Louise, Nadine, Imani, Lori, Tiy, Molly, and Ryan, continually build me up and are intellectual and political sounding boards. I also could not have completed this book without support from my closest friends scattered across the United States, many of whom may not want to be named, but you know who you are, including Louise, Bill and Lauren Godfrey, Gia, Amy, Jenny, Christy, Tamsin, and Sandra. These lifelong friends (and some of their parents and children) from high school, college, corporate America, and graduate school, are incredibly special to me, and I hope they know how deeply appreciated they are, despite the quality time I have diverted away from them and their families to write this book.

The passion in this research was ignited in a research group led by Dr. Lisa Nakamura at Illinois, without whose valuable conversations I could not have taken this work to fruition. My most trustworthy sister-scholars, Sarah T. Roberts and Miriam Sweeney, kept a critical eye on this research and pushed me, consoled me, made me laugh, and inspired me when the reality of how Black women and girls were represented in commercial search would deplete me. Sarah, in particular, has been a powerful intellectual ally through this process, and I am grateful for our many research collaborations over the years and all those to come. Our writing partnerships are in service of addressing the many affordances and consequences of digital technologies and are one of the most energizing and enjoyable parts of this career as a scholar.

There are several colleagues who have been helpful right up to the final stages of this work. They were subjected to countless hours of reading my work, critiquing it, and sharing articles, books, websites, and resources with me. The best thinking and ideas in this work stem from tapping into the collective intelligence that is fostered by surrounding oneself with brilliant minds and subject-matter experts. I am in awe of the number of people it takes to support the writing of a book, and these are the many people and organizations that had a hand in providing key support while I completed this research. Undoubtedly, some may not be explicitly named, but I hope they know their encouragement has contributed to this book.

I am grateful to my editors, Ilene Kalish and Caelyn Cobb at New York University Press, for bringing this book to fruition. I want to thank the editors at Bitch magazine for giving me my first public-press start, and I appreciate the many journalists who have acknowledged the value of my work for the public, including USA Today and the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Professors Sharon Tettegah, Rayvon Fouché, Lisa Nakamura, and Leigh Estabrook were instrumental in green-lighting this research in one form or another, at various stages of its development. Important guidance and support along the way came from my early adviser, Caroline Haythornthwaite, and from the former dean of the Information School at Illinois, John Unsworth.

Dr. Linda C. Smith at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign continues to be an ardent supporter, and her quiet but mighty championing of critical information scholars has transformed the field and supported me and my family in ways I will never be able to fully repay. This research would not have happened without her leadership, compassion, humor, and incredible intelligence, for which I am so thankful. I suffer in trying to find ways to repay her because what may have been small gestures on her part were enormous to me. She is an incredible human being. I want to thank her for launching me into my career and for believing my work is a valuable and original contribution, despite the obstacles I faced or moments I felt unsupported by those whose validation

I thought I needed. Her stamp of approval is something I hold in very high regard, and I appreciate her so very much.

Dr. Sharon Tettegah taught me how to be a scholar, and I would not have had the career I’ve had so far without her mentorship. I respect her national leadership in making African American women’s contributions to STEM fields a priority and her relentless commitment to doing good work that makes a difference. She has made a tremendous difference in my life.

I am indebted to several Black feminists who provided a mirror for me to see myself as a scholar and contributor and consistently inspire my love for the study of race, gender, and society: Sharon Elise, Angela Y. Davis, Jemima Pierre, Vilna Bashi Treitler, Imani Bazzell, Helen Neville, Cheryl Harris, Karen Flynn, Alondra Nelson, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Mireille Miller-Young, bell hooks, Brittney Cooper, Catherine Squires, Barbara Smith, and Janell Hobson, some of whom I have never met in person but whose intellectual work has made a profound difference for me for many years. I deeply appreciate the work and influence of Isabel Molina, Sandra Harding, Sharon Traweek, Jean Kilbourne, Naomi Wolfe, and Naomi Klein too. Herbert Schiller’s and Vijay Prashad’s work has also been important to me.

I was especially intellectually sustained by a number of friends whose work I respect so much, who kept a critical eye on my research or career, and who inspired me when the reality of how women and girls are represented in commercial search would deplete me (in alphabetical order): André Brock, Ergin Bulut, Michelle Caswell, Sundiata Cha-Jua, Kate Crawford, Jessie Daniels, Christian Fuchs, Jonathan Furner, Anne Gilliland, Tanya Golash-Boza, Alex Halavais, Christa Hardy, Peter Hudson, John I. Jennings, Gregory Leazer, David Leonard, Cameron McCarthy, Charlton McIlwain, Malika McKee-Culpepper, Molly Niesen, Teri Senft, Tonia Sutherland, Brendesha Tynes, Siva Vaidhyanathan, Zuelma Valdez, Angharad Valdivia, Melissa Villa-Nicolas, and Myra Washington. I offer my deepest gratitude to these brilliant scholars, both those named here and those unnamed but cited throughout this book.

My colleague Sunah Suh from Illinois and Jessica Jaiyeola at UCLA helped me with data collection, for which I remain grateful. Drs. Linde Brocato and Sarah T. Roberts were extraordinary coaches, editors, and lifelines. Myrna Morales, Meadow Jones, and Jazmin Dantzler gave me many laughs and moments of tremendous support. Deep thanks to Patricia Ciccone and Dr. Diana Ascher, who contributed greatly to my ability to finish this book and launch new ventures along the way.

I could not have completed this research without financial support from the Graduate School of Education & Information Studies at UCLA, the College of Media at Illinois, the Information School at Illinois, and the Information in Society fellowship funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services and led by Drs. Linda C. Smith and Dan Schiller. Support also came from the Community Informatics Initiative at Illinois. I am deeply appreciative to the Institute for Computing in the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (I-CHASS) and the leadership and friendship of Dr. Kevin Franklin at Illinois and key members of the HASTAC community for supporting me at the start of this research. Illinois and UCLA sent fantastic students my way to learn and grow with as a teacher. More recently, I was sustained and supported by colleagues in the Departments of Information Studies, African American Studies, and Gender Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), who have been generous advocates of my work up through the publication of this book. Thank you to my colleagues in these world-class universities who were tremendously supportive, including my new friends at the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Southern California under the leadership of the amazing Dr. Sarah Banet-Weiser, whose support means so much to me.

Many people work hard every day to make environments where I could soar, and as such, I could not have thrived through this process without the office staff at Illinois and UCLA who put out fires, solved problems, made travel arrangements, scheduled meetings and spaces, and offered kind words of encouragement on a regular basis.

Support comes in many different forms, and my friends at tech companies Pixo in Urbana and Pathbrite in San Francisco—both founded by brilliant women CEOs—have been a great source of knowledge that have sharpened my skills. I appreciate the collaborations with the City of Champaign, the City of Urbana, and the Center for Digital Inclusion at Illinois. The Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies in Washington, D.C., gave me great opportunities to learn and contribute as well, as did the students at the School for Designing a Society and the Independent Media Center in Urbana, Illinois.

Thank you to the brilliant #critlib librarians and information professionals of Twitter, which has been a powerful community of financial and emotional support for my work. I am immensely grateful to all of you.

Lastly, I want to thank those on whose shoulders I stand, including my mother. It is she who charted the course, who cut a path to a life unimaginable for me. When she passed, fifteen years ago, most of my reasons for living died with her. Every accomplishment in my life was to make her proud, and I had many dreams that we had cooked up together still to be fulfilled with her by my side. Her part in this work is at the core: she raised me as a Black girl, despite her not being a Black woman herself. Raising a Black girl was not without a host of challenges and opportunities, and she took the job of making me a strong, confident person very seriously. She was quite aware that racism and sexism were big obstacles that would confront me, and she educated me to embrace and celebrate my identity by surrounding me with a community, in addition to a fantastically diverse family and friendship circle. Much of my life was framed by music, dolls, books, art, television, and experiences that celebrated Black culture, an intentional act of love on her part to ensure that I would not be confused or misunderstood by trying to somehow leverage her identity as my own. She taught me to respect everybody, as best I could, but to understand that neither prejudice at a personal level nor oppression at a systematic level is ever acceptable. She taught me how to critique racism, quite vocally, and it was grounded in our own experiences together as a family. I am grateful that she had the foresight to know that I would need to feel good about who I am in the world, because I would be bombarded by images and stories and stereotypes about Black people, and Black women, that could tear me down and harm me. She wanted me to be a successful, relevant, funny woman—and she never saw anything wrong with me adding “Black” to that identity. She saw the recognition of the contributions and celebrations of Black people as a form of resistance to bigotry. She was never colorblind, and she had a critique of that before anyone I knew. She knew “not seeing color” was a dangerous idea, because color was not the point; culture was. She saw a negation or denial of Black culture as a form of racism, and she never wanted me to deny that part of me, the part she thought made me beautiful and different and special in our family. She was my first educator about race, gender, and class. She always spoke of the brilliance of women and surrounded me with strong, smart, sassy women like my grandmother Marie Thayer and her best friend, my aunt Darris, who modeled hard work, compassion, beauty, and success. In the spirit of these strong women, this work has been bolstered by the love and support of my mother-in-law, Alice Noble, who consistently tells me she’s proud of me and offers me the mother-love I still need in my life.

My mentors, Drs. James Rogers, Adewole Umoja, Sharon Elise, Wendy Ng, Francine Oputa, Malik Simba, and professor Thomas Witt-Ellis from the world-class California State University system, paved the way for my research career to unfold these many years later in life.

Anything I have accomplished has been from the legacies of those who came before me. Any omissions or errors are my own. I hope to leave something helpful for my students and the public that will provoke thinking about the impact of automated decision-making technologies, and why we should care about them, through this book and my public lectures about it.

Introduction

The Power of Algorithms

This book is about the power of algorithms in the age of neoliberalism and the w

ays those digital decisions reinforce oppressive social relationships and enact new modes of racial profiling, which I have termed technological redlining. By making visible the ways that capital, race, and gender are factors in creating unequal conditions, I am bringing light to various forms of technological redlining that are on the rise. The near-ubiquitous use of algorithmically driven software, both visible and invisible to everyday people, demands a closer inspection of what values are prioritized in such automated decision-making systems. Typically, the practice of redlining has been most often used in real estate and banking circles, creating and deepening inequalities by race, such that, for example, people of color are more likely to pay higher interest rates or premiums just because they are Black or Latino, especially if they live in low-income neighborhoods. On the Internet and in our everyday uses of technology, discrimination is also embedded in computer code and, increasingly, in artificial intelligence technologies that we are reliant on, by choice or not. I believe that artificial intelligence will become a major human rights issue in the twenty-first century. We are only beginning to understand the long-term consequences of these decision-making tools in both masking and deepening social inequality. This book is just the start of trying to make these consequences visible. There will be many more, by myself and others, who will try to make sense of the consequences of automated decision making through algorithms in society.

Part of the challenge of understanding algorithmic oppression is to understand that mathematical formulations to drive automated decisions are made by human beings. While we often think of terms such as “big data” and “algorithms” as being benign, neutral, or objective, they are anything but. The people who make these decisions hold all types of values, many of which openly promote racism, sexism, and false notions of meritocracy, which is well documented in studies of Silicon Valley and other tech corridors.

Algorithms of Oppression

Algorithms of Oppression